There are certain books that I think don’t always get their just due. They are given the dubious distinction of “children’s classic.” Perhaps in olden days, “boy’s adventure.” Or maybe now, “young adult.” Probably the most familiar example are the Harry Potter books. Sure, children loved them. I was teaching middle school when they first exploded on the scene. And I was aghast at the controversy; children were willingly, eagerly reading long books….this was a problem? Let’s be honest; it’s not like Harry Potter was only read by children. The same goes for films such as The Wizard of Oz or nearly any Disney film, from Cinderella to Mary Poppins to Toy Story. Sure, you may have made your first journey down the Yellow Brick Road when you were a child, but decades later, you still relish the experience….maybe with an even deeper appreciation.

Now, with films, the “children’s literature” categorization doesn’t seem to be a dubious distinction. Wizard of Oz is always on lists of the greatest films ever; Mary Poppins, too. Both are considered examples of great filmmaking. But it seems with literary works, the crown of “children’s literature” is a patronizing one. Sure, it’s good….if you’re into that thing. It’s not real literature, you know…it’s just the kiddy stuff. It’s why, when you talk the great French writers of the 19th century, you talk Dumas, Hugo, maybe Stendhal. I put “maybe” with Stendhal, because, truthfully, I never finished The Red and the Black. But you know who you rarely, if ever, see put in that same group? Jules Verne. Never mind he gave the world an absolute page-turner in Around the World in 80 Days, not to mention creating Captain Nemo. Not good enough, apparently. While we all probably agree that Verne is one of the fathers of science fiction, that’s not enough to make him part of the canon of classic literature. Oh, he’s good….but maybe as writer of fantastic, juvenile fiction. Let’s keep ol’ Jules separate from the real writers: Hugo and Dumas, for example.

Well, as I’ve written before, Verne’s Around the World in 80 Days is one of a small group of books I hold dearer than any about anything ever written not counting the Bible. I’ve lost count of how many times I’ve read it in my lifetime. And despite always knowing the outcome, I’m still enthralled in Phileas Fogg’s spur-of-the-moment wager to cross the globe. I’ve read Les Miserables once. I gave up on both Dumas and Stendhal. But Jules Verne and his merry band of Fogg, Passepartout, Aouda and Fix…..that just keeps me coming back, again and again. Sure, it’s much shorter than Hugo, I’ll grant you that. And it’s easier to read. But maybe that’s just it. Verne tells a story that I love. It’s enjoyable. No matter how many times I’ve read it, I’m always sad when it’s over. I want more adventures of Fogg and Co.! There’s no sigh of relief that I just finished that tome. It’s not an accomplishment reading Verne; its total enjoyment. Fogg’s journey is a competition, but for me, it’s all pleasure. You can keep Jules Verne out of your canon of greatness. You can reduce him to the double-edged sword of “juvenile class.” Just know that I’ll skip your greats every time, to once again commence globe-transversing wager.

Even the cover screams “Kiddie.” You deserve a better fate, Phileas Fogg!

Another author who seems consigned to a similar fate, and the subject of today’s blog, is Robert Louis Stevenson. Interesting that they were roughly contemporaries. Verne came on the scene before Stevenson, and Around the World in 80 Days was published 10 years prior to Stevenson’s Treasure Island, the book that made him. But it is interesting that these two storytellers (for that’s what they are, and that’s not a slight. They are storytellers of the very first order) have existed somewhat outside of the canon of classic literature. Again, they are considered authors of those dreaded two words of condescending denigration, “juvenile literature.”

Yet, here’s the thing…the reading public has never lowered its thoughts on Verne and Stevenson. Even if you’ve never read 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, you’ve probably heard of Captain Nemo. You may not have read these books, but you’ve probably heard of Journey to the Center of the Earth or From Earth to the Moon. Can you name a character from a Henry James novel? After Tess, what other Thomas Hardy characters jump to mind?

With Stevenson, this is even greater the case. And it really comes from one book, Treasure Island. It is absolutely shocking how much influence that work has had. The most obvious case is a fast food bastion that specializes in seafood, bearing the name of Stevenson’s fabulous character. I am, of course, referring to

But Treasure Island is so much more than just the inspiration for fried fish and hushpuppies! So much of what we associate with pirates has come from it. A treasure map with X marking the spot. Pirates serving a companion with the dreaded Black Spot. A pirate with a missing leg and a talking parrot upon his shoulder. All of those are not from pirate lore. No…they’re from Robert Louis Stevenson. Seriously. Look it up. You could dare say, until Johnny Depp came along, the popular conception of a golden age buccaneer is from the mind of late 19th century Scottish writer….who was writing well over a century since piracy had faded into memory. Children’s fiction my foot…..err, missing foot, in the case of Treasure Island‘s most legendary contribution. Now granted, a one legged protagonist/antagonist/antihero, whatever you want to label him, in a nautical tale is not original to Stevenson. Melville’s Moby Dick, featuring ivory-legged Captain Ahab, predates Treasure Island by 3 decades. But I ask you….and please be honest, for those who have read both works, who do you prefer, Ahab or Long John Silver? They’re both remarkable creations, and associations with either of them could be potentially dangerous to your livelihood. And I’m not saying Treasure Island is greater literature than Moby Dick….well, let’s come back to that. I’m just saying, ol’ Long John sure seems a more fabulous character than Ahab….or at least one you can have a good time with. That is before he double-crossed you.

Doesn’t look like much fun to sail with this one-legged captain.

But this one, on the other hand…err, leg….

At some point in our popular awareness, we became familiar with how a pirate talks. I’ve heard it said some actually trace that back to Robert Newton’s portrayal of Long John Silver, in the 1950 Disney version of Treasure Island. I haven’t seen that film since I was very young. And interestingly enough, Newton would, a few years later, portray Inspector Fix in Around the World in 80 Days. You see….it’s all connected! Anyway, the phrase “Arrrr” never appears in Stevenson. But I challenge you to read this bit of Silver’s speech, and tell me if you don’t hear in your head the stereotypical pirate voice:

Gentlemen of fortune [returned the cook] usually trusts little amongst themselves and right they are, you may lay to it. But I have a way with me, I have. When a man brings a slip on his cable – one as knows me, I mean – it won’t be in the same world as old John. There was some that was feared of Pew, and some that was feared of Flint; but Flint his own self was feared of me. Feared he was, and proud. They was the roughest crew afloat, was Flint’s; the devil himself would have been feared to go to sea with them. Well, now, I tell you, I’m not a boasting man, and you seen yourself how easy I keep company; but when I was quartermaster, lambs wasn’t the word for Flint’s old buccaneers. Ah, you may be sure of yourself in old John’s ship.

Again, when Stevenson wrote this, pirates were long past. It had been well over a 100 years; it’s not like he had the opportunity to sit down an interview a veteran of plundering the Caribbean. All this came from his imagination. And yet when you read that, do you not hear the pirate voice? The only alternative for me might’ve been Alfred P. Doolittle from My Fair Lady, with his unique choice of words. But save that option, that’s what we consider to be authentic pirate speech. But it’s not historical, it’s not of the record, it’s wholly Robert Louis Stevenson. Another contemporary of Stevenson’s, and one in a similar plight, is Arthur Conan Doyle. Sure, the Sherlock Holmes stories are given a high valuation….but they are also regarded in a niche. They’re masterful detective stories….but they’re not really the same high art as true literature. But again, what other literary creations have so endured in the public conscious as Holmes, Watson, Moriarty, Irene Adler, Inspector Lestrade and their like? With Stevenson, it’s not just the character of Long John Silver who endures….it’s our entire conception of what a pirate is. It’s all his creation!

Robert Louis Stevenson at work. To think, what we accept of pirates sprung from that setting and not the Spain Main!

In case you hadn’t guessed already, I just recently re-read Treasure Island. I think I probably had read it as a kid, but the last time I had gone through it was sometime when I was an undergrad. I don’t know whey I had a copy. I must’ve picked up at some point, thinking it was important to have. And I also don’t know why I, just a month or so ago, decided to pick it up off my shelf. I think it probably had to do with (surprise, surprise) Jules Verne. I had bought 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea at a used book sale last summer, and that too, I had not read since undergrad days (so, some 20 odd years ago). I reread 20,000 and soon realized how much I had forgotten. Its a very good story, but some of it doesn’t hold up as well as the rest. The narrative….great! Spell-binding! Enrapturing! The cataloging of every fish and underwater fauna encountered…yeah, that doesn’t really do it for me. But, of course, Verne was writing at a time when the general public had no idea what lay beneath the waves, so I guess it’s excusable.

And so, with similar motivations, I revisited Treasure Island for the first time in two decades. This one, I remembered more of. I remembered the action starting in a tavern, the delivery of the Black Spot, the mutiny of the crew, Jim sailing the ship, the crazed marooned sailor, and that Long John gets away. But what I didn’t realize was this: Treasure Island is perfection in the novel/novella form. Let me say that again: it is PERFECTION. There is no way Robert Louis Stevenson could have improved it. It is a total and complete masterpiece. Every scene, every setting, every character advances the story. Nothing is wasted or is filler. The story is under 195 pages, because it says what it has to say. If the lack of backstory on Dr. Livesey, Jim Hawkins, and Squire Trelawney, or any detailed history of Capt. Flint’s original voyages is what bars Treasure Island from the accepted canon, then I side with Stevenson. There have been numerous works, the cable show Black Sails the most recent, that attempt to fill in the pre-story. Sure, it’s fun to see Ben Gunn marooned on the island, and to see how the buccaneers lost body parts (Black Dog his fingers, Pew his sight, and Silver a leg). But not knowing who Captain Flint was, where his treasure came from, and how the crew was dispersed, is not necessary to Stevenson. All we need to know is that a hard drinking, shabby looking seafaring man has come to stay at the Admiral Benbow Inn, that he has a sea trunk and that he’s away on the lookout for others. That’s all the backstory we need…and Stevenson is off and running.

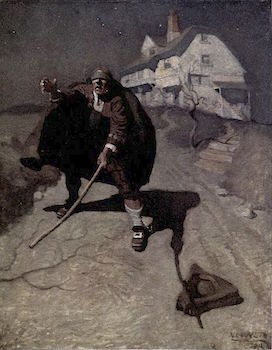

Billy Bones, the seafaring lodger at the Admiral Benbow. What’s his backstory?

Not only does every character have a role, they never overstay their welcome. They play their part on the stage, and then Stevenson moves on. Let’s take a few examples:

Jim Hawkins’ parents: we never see his father, but we know he is sick and succumbs to this. His mother escapes before the pirates ransack the Admiral Benbow. I’ll grant you, it may seem a little odd that Jim doesn’t dwell too much on his father’s passing, but a.) he is a young man (I don’t think his age is ever given) and more importantly, b.) Stevenson has a specific story to tell. The Hawkins family is only a smart part of it. What we know is, with no father, and with his mother’s permission given, there’s nothing stopping him from joining the voyage to claim Flint’s treasure.

So many of the pirates themselves:

We saw “Black Dog” twice and both times he advances the narrative. He first shows up at the Admiral Benbow to deliver the Black Spot, and then we see him again, when Jim Hawkins recognizes him in Long John Silver’s harbor restaurant in Bristol. Once he bolts from the joint, he’s gone from the story. But he didn’t go without making his presence felt. When Hawkins (and by default, us) recognize Black Dog in Silver’s restaurant, it’s our first cue that something is not right.

The same goes for Blind Pew. It originally struck me that someone who seems to be, easily, the most evil of all the villains, is so easily written off. He’s run over by a carriage, an ignominious end for someone who seems like he’s the leader of the Admiral Benbow marauders. But in reality, Stevenson had no more use for him. He shows up early on, to threaten Jim Hawkins with his life if he doesn’t help. His job is to inform us just what kind of people Flint’s old crew are. When we first meet Long John Silver, he’s amiable enough. Even when Jim overhears the mutiny while in the apple barrel, we don’t really know just what Silver and his ilk are capable of. It’s all been talk, for the most part. We’ve had Capt. Smollet’s misgivings of his crew, and we’ve had the disappearance of the first mate. But there hasn’t been any real violence to this. Pew would be completely out of place once the action moves to Bristol or the schooner Hispaniola. We already know how evil he is, and by “we”, I mean our narrator, Jim Hawkins. Stevenson had no further use of him, so why not be rid of Pew in, quite possibly, the most ridiculous fashion possible?

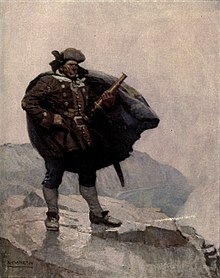

Pew, before his encounter with horses

It’s fascinating to me how Stevenson drops characters out of the narrative, once their function is complete. Take the good Squire Trelawney, for whom much of the blame should go for the entire predicament. He finances the expedition, and despite the warnings of the wise Dr. Lively, he cannot keep his mouth shut about what their intentions are. It is because of him that the word is out about an attempt to recover Flint’s treasure. It’s also because of him that so many pirates are able infiltrate the crew, due to the Squire overruling Capt. Smollet’s objections on the personnel. Then, once the mutiny is underway, Stevenson gives him another important role: we’re told he’s an excellent shot. And when the heroes are aboard their jollyboat, making for the stockade, it is the Squire’s accuracy that takes out a pirate aboard the Hispaniola. What a vital turn of events that is, for when Jim Hawkins boards the ship a day later, he’s only up against one, rather than three. But once that’s done, so is the Squire. We know he makes it back, nothing bad happens to him from there on…..but he doesn’t play a major role. Stevenson’s story is so tight, he doesn’t waste time with scenes/characters that aren’t advancing the narrative. Talk about discipline!

There are plenty more examples. O’Brien, the pirate with the red cap aboard the Hispaniola. We seem him from a distance, and thats about it. By the time Jim gets aboard the ship, O’Brien is just a corpse. So why include this detail? It’s so we know just how dangerous a man Israel Hands, the other pirate on board, is. Sure, Israel will teach Jim how to navigate the ship around the Island. But we also need to know just what kind of man he is. O’Brien being nothing more than corpse does that for us. If Israel Hands will not hesitate to kill one of his mates, then we should have no surprise that he’ll turn against Jim Hawkins. And here you have to salute Stevenson for his economy. He could’ve had Jim be there, to see Hands and O’Brien go after each other. But he knows that’s not necessary. When Jim comes upon the scene, the only living pirate is Hands. The odds are now one against one. But O’Brien being corpse doesn’t just even the playing field for Jim, it lets us know what to expect from Israel Hands. Again, Robert Louis Stevenson using every character for a purpose.

One more example of each character serving a point, and then I’ll move on (just as Stevenson does, after the role is played). If Long John Silver is the most memorable character in Treasure Island, and I think we’d all agree he is, then the second most memorable has to be Ben Gunn. You remember Ben Gunn; he’s also a member of Flint’s crew, but unlike the rest of the pirates, he’s been marooned on Treasure Island for three years. I recently read Robinson Crusoe and I recall reading that Stevenson thought very highly of that work. Yet, you have to think Ben Gunn is Stevenson’s answer to that. You may recall that Robinson Crusoe is on the Island of Despair for something like 17 years before he meets Friday. Yet, throughout the entire narrative, Crusoe is in his right mind, so much so that he is ready to plot how to take out an invasion of mutineers. Not so the case with Ben Gunn. He’s pretty much out of his mind when Jim encounters him, and rather than clothes made from goat skins, he’s in tatters from what he could find. And may I remind you, Ben Gunn has only been alone for three years, nothing compared to what Crusoe was.

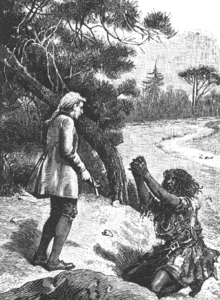

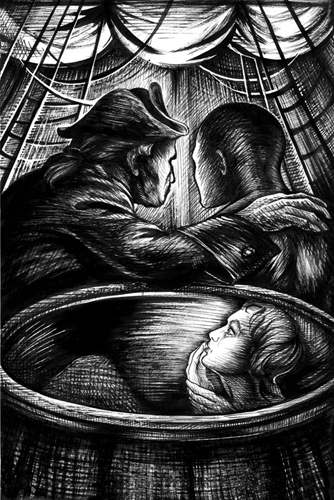

Ben Gunn pleads with Jim Hawkins

But though Gunn is memorable, he really only appears in one chapter. And that is again Stevenson’s genius of economy. He introduces Gunn so that we know our heroes and the pirates are not alone on the Island. And with that established, we now have a deus ex machina that can resolve the plot. From when he tells his unfortunate tale to Jim, we know that Ben Gunn has a score to settle with Long John Silver and his gang. And because he’s been on the Island for three years, we can imagine he knows every inch of it. It allows for our heroes to have a fighting chance, as we found out it was Gunn who takes out one of the pirates, and not the Captain, the Doctor and the Squire. We don’t see it happen, but because Jim has already encountered Gunn, we can believe it happening. And that’s why the ultimate deus ex machina works. We really haven’t seen Ben since Jim’s initial encounter, but there’s no reason to not believe that he had already found Flint’s treasure before the Hispaniola ever laid anchor off Skeleton Island. We don’t need a scene of Gunn helping the Doctor and the Squire dig up the treasure. We know, from his conversation with Jim, that Ben is familiar with the treasure. He was marooned because he couldn’t show a different crew where it was. But now he’s promising Jim he’ll be rich. So why should we be surprised when Silver and his gang come to the spot marked upon the map, only to find the treasure missing? Stevenson has already provided us enough evidence that there’s no reason to question Ben Gunn is responsible, even though we never saw it. That’s again Stevenson’s mastery. Ben Gunn only really appears in one chapter, but because of those few pages, his presence is felt throughout the rest of the story. And I didn’t even mention how Ben telling Jim about a home made coracle makes it possible for the latter to board the Hispaniola. Again, every character serves a purpose.

From the 1950 Disney version

And it’s not just the characters that Stevenson is economic with. I mentioned how, in 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, Jules Verne takes his time in telling the readers about all the fish and fauna his characters encounter. Stevenson does not make the same mistake. When Jim first gets onto the Island, he immediately bolts away from Silver and his gang. Jim (well, actually Stevenson) gives us a description of tall, wide oak trees, surrounding a thicket, with a marsh nearby. As we find out there’s a reason he’s being so descriptive. It’s because this makes the perfect setting for the next scene. The thicket is a place where Silver has brought along an uncorrupted crew member, to make his sales pitch. And because we know it is surrounded by thick oaks, there’s no reason to not believe Jim’s ability to witness the entire scene. This is one of the only times Stevenson is thoroughly descriptive of a setting and its all because it makes this important scene believable. If not for the described oaks, how could we believe Jim Hawkins is able to eavesdrop? How vital is this scene? It’s absolutely essential, for this is where we see just who Long Silver might really be. After all, this is where Long John kills the crew member Tom, when he is not wiling to join the mutiny. Other times, Stevenson isn’t as particular about the setting. But then again, not every moment is a one of illumination of such a major character.

There is so much in the plot of Treasure Island that is left out. How did the argument go down between Jim Hawkins and his mother, which allowed him to make the voyage? And what was the voyage like? There is almost nothing about it at all. We assume, as a cabin boy, Jim learned much of sea life. Heck, we can assume that’s how he (with a slight assistance from Israel Hands) is able to pilot the Hispaniola around the island. But Stevenson spares us the details. He also leaves out any conversations/character development along the way. We hear the crew seems to be working hard, and we also learn that the first mate is, at first, drinking and then later, disappeared. But as for conversations between Jim and Silver, we have to imagine. We get no more plot development till the night before landing, when Jim falls into the apple barrel and discovers the plot.

I do wonder why Stevenson chose to be so economical, only giving us characters, scenes and descriptions that advance the story. We do know that he envisioned Treasure Island as being a work for boys. But to my thinking, his economic writing style is still not just a concession to young attention spans. No, it’s more than that….really, it’s the mark of a master. Treasure Island may have been Stevenson’s breakthrough work, but unlike, say, Oliver Twist, which isn’t as fully developed a story as Dickens’ later works, there’s nothing amiss with TI. If I were teaching a course on creative fiction, I would make Treasure Island mandatory reading. The taut nature of the writing, where everything matters and nothing is filler, can be example for anyone wanting to take up the literary arts.

Jim in the apple barrel, overhearing the plot

It is fascinating to me that, for a book that so created our popular conception of pirates, how much of pirate tradition is actually missing. For starters, the setting. Though Stevenson does’t give the date, it’s commonly accepted that it happens sometime in the mid to late 18th century, probably in the time before the American Revolution. Piracy had somewhat wound down by then, the notorious Blackbeard exiting this world in 1718. These pirates, survivors of Flint’s crew, are the remnants of an age gone past. Look, they don’t even have their own ship! They have to mutiny to take someone else’s. Furthermore, the first three pirates we meet (Billy Bones, Black Dog and Pew) are all on the land. The familiar pirate trope of walking the plank are nowhere to be found. Interestingly, the majority the action takes place on land. And though Israel Hands is supposedly good at manning “Long Tom”, the cannon on the Hispaniola, once our heroes reach the stockade, they are safely out of its reach. And then there’s Silver himself. He was no captain. When we meet him, he’s a cook in a Bristol tavern. In Flint’s day, he was the quartermaster. He is only a captain during the mutiny and it’s important to observe, his captaincy occurs strictly on the Island. We never get Captain John Silver, striding one-legged upon his own vessel. It’s reminiscent of those later Westerns, like The Wild Bunch where the career gunslingers/outlaws find themselves in a world that has moved on from them. So it was with Stevenson’s pirates. Pew a beggar and Silver a cook. They’ve fallen a long way since wreaking havoc on the seas.

And then there is Long John Silver himself. You have to think Robert Louis Stevenson knew what he was doing when created the character. Silver completely dominates every scene he is in. Even when he doesn’t speak, we still feel his presence. When Jim is preparing to launch the coracle, he describes how he sees Silver in a jollyboat going back from the Hispaniola to the Island. He has more dialogue than any character and virtually all of it is memorable. As mentioned earlier, every sentence of Silver’s crackles with what assume a pirate sounds like. Here’s another great example:

“There!” he cried, “That’s what I think of ye! Before an hour’s out, I’ll stove in your old blockhouse like a rum puncheon. Laugh, by thunder, laugh! Before an hour’s out, you’ll laugh upon the other side. Them that die’ll be the lucky ones.”

Everything about Long John Silver commands our attention: naturally the one leg, but how he also is described as moving well on his crutch. But it’s what we don’t know about Silver that makes him so mesmerizing. What can we say about him, other than he’s loyal only to himself. He does seem to genuinely like Jim Hawkins, both before the mutiny breaks out and later, when Jim stumbles upon the pirates in possession of the stockade. We know he’s smarter than the average pirate. When Jim is in the apple barrel, he hears Silver describe how everyone else of Flint’s crew, like Pew and Billy Bones, had been reduced to poverty, while he made out alright. His threat to Captain Smollet, which I quoted above, was not idle talk. His pirates attacked repeatedly. And you’ve already read where I recounted his killing of a sailor who wouldn’t join the mutiny. Silver looks out for no one more than himself. The last 30 pages or so are such a wondrous portrayal. In his negotiations with Doctor Lively, it appears Silver knows the plot is lost. One has to wonder if he suspects the treasure really isn’t there, unlike the rest of the pirate band. Silver is already talking to both Jim and the Doctor about testifying to his reformed conduct. The treasure, at this point, is less important, than keeping out of the gallows, the fate of all pirates.

But Stevenson isn’t content to let us come to the conclusion that Silver is about to go soft. We see how he calmly and confidently puts down a mutiny against his leadership, refuting the Black Spot, and doing all of it without violence. And if we are to believe he knows the treasure isn’t there, Stevenson gives us this incredibly vivid sequence:

Silver hobbled, grunting, on his crutch; his nostrils stood out and quivered; he cursed like a madman when the flies settled on his hot and shiny countenance; he plucked furiously at the line that held me to him, and, from time to time, turned his eyes upon me with a deadly look. Certainly he took no pains to hide his thoughts; and certainly I read them like print. In the immediate nearness of the gold, all else had been forgotten; his promise and the doctor’s warnings were both things of the past; and I could not doubt that he hoped to seize upon the treasure, find and board the Hispaniola under cover of night, cut every honest throat about that island, and sail away as he had at first intended, laden with crimes and riches.

What great writing by Stevenson. For those familiar with the film Treasure of Sierra Madre, its like the gold sickness that corrupts Fred C. Dobbs. Silver is like a shark that has tasted blood in the water and is in a feeding frenzy. It’s an unforgettable image. But Stevenson doesn’t dwell on it. When the treasure if found to be gone, he (or Jim, narrating) tells us that Silver recovers from shock/disappointment almost instantly. While the rest of the pirates are about to become hysterical and turn against Silver again, the latter has already planned his next move. And when the ambush comes, Silver has wasted no time in changing his loyalties.

It’s fitting that Stevenson leaves Long John Silver’s fate unknown. Ben Gunn enables him to escape when the Hispaniola is docked in Spanish America. He’s not going to risk going back to England, where he may have to face charges. Gunn says that it was for everyone’s benefit, as Silver would have killed them all. Why wouldn’t he? His loyalties are only to himself. I’d like to think he’d have spared Jim Hawkins…..but there’s no reason to believe that. It’s better Silver went his own way. We don’t get a definitive answer on how much a villain he is; should he have tried to take the ship again, then there would be no doubt. Robert Louis Stevenson only lived to age 44; who knows, had he lived longer, would h have revisited his most fabulous creation. Leave it for others to decide what became of Long John Silver. Stevenson gave us enough for each of us to dream.

It’s a cruel fate that Treasure Island is relegated as a juvenile classic, whereas Mark Twain’s The Adventure of Huckleberry Finn is regarded as a literary masterwork. Both came out within a year of each other and, in my opinion, the comparison is not close. Unlike TI, Finn is riddled with storylines and characters that go nowhere. Tom Sawyer’s appearance in Arkansas, and the ridiculous challenges he creates to freeing Jim drag on. There are numerous episodes along the Mississippi that, while interesting, don’t rely advance a storyline….unless the storyline is how mean, two-faced and dishonest people can be. Bu I think that’s why Finn is held higher than TI. Despite all of its narrative faults, and there are many, Finn is striving to say something. It’s a commentary on the hypocrisy of civilization, and that Huck and Jim, by operating outside of it, are the truly noble characters. Treasure Island doesn’t attempt to make any statement about human nature and society; rather, it aims to tell a rousing story in a direct, clear manner. And does it ever deliver! There’s no larger purpose, it’s just the story of Jim Hawkins and his guardians, and their battle with pirates for treasure. That’s all there is. Nothing more than that.

So does that mean Treasure Island isn’t great literature? I guess it depends on your criteria. For me, TI is an unquestioned triumph in terms of craftsmanship. Stevenson’s economic storytelling is simply perfection. His story grips you and it’s as much a page-turner as anything I’ve read that’s over 135 years old. It’s a textbook in how to tell a story. If the lack of a statement on the human condition disqualifies it from great literature, so be it. But does it really lack that statement? Let’s take a closer, final look:

Flint’s old crew can’t be reformed. They burn through their money and are hungry for more. That still happens.

The Squire can’t keep anything a secret. Check.

The character of Long John Silver: willing to sell anyone out at any time, for his own benefit. Why, I’d say that’s a dark human trait.

So while Treasure Island may not be preachy, don’t be so quick to write it off as having nothing bigger to say. Perhaps its problem is, it’s just such a good story that the narrative overshadows anything else. That’s not necessarily a bad thing.

But if there is anything to question Treasure Island’s relevance, this is the answer; what would we think of pirates today if Robert Louis Stevenson had never existed? No Black Spot! No parrot on the shoulder! Would the dialogue be different? That alone is enough to justify Treasure Island’s worth. But the fact that it’s a model of tight storytelling, one without peer…..well, that’s a classic in my book. And just like Jules Verne and Around the World in Eighty Days, it’s a journey I’ll be returning to again in my literary life.

Bravo and thank you, Robert Louis Stevenson, and to Long John Silver….till we meet again!

Treasure Island, as drawn by Robert Louis Stevenson